Foreign Workers and Public-Sector Careers: Kuwait’s Labour Risks

Primary Analyst: Amanda Miknev

Team Leader: Duncan Spilsbury

Kuwait’s standing on both the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index and the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness rankings have been falling throughout 2017. Recent economic and employment initiatives by the Kuwaiti government to spur career development among nationals have altered the country’s international business arena.

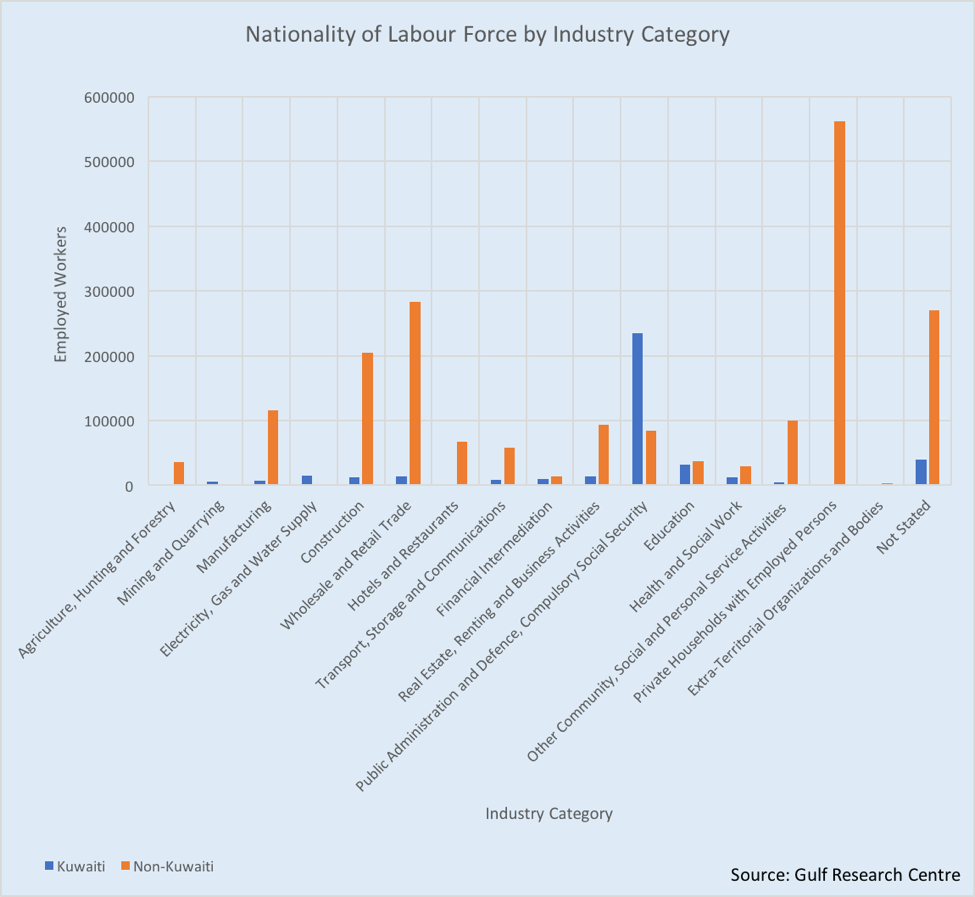

Kuwait’s labour force nationalization policies and subsequent special funding has led to a bloated public administration sector. The country’s robust social welfare system enables nationals to receive benefits and to work in subsidised government-owned industries. Nationals account for 86.6% of the public-sector workforce while only 6.4% of nationals work in the private sector. Inefficient government bureaucracy was cited by the Global Competitiveness Report (GCR) as the most problematic factor for business in Kuwait during 2015.

Expatriate labourers dominate the current Kuwaiti economy, accounting for 83% of the total workforce. The Public Authority of Manpower (PAM) announced a series of changes to the expatriate admission process scheduled for 2018. Notably, Kuwait will no longer recruit expatriate workers with post-secondary education that are under the age of thirty. The PAM’s decision to reject young, educated foreign workers may present less competition for Kuwaiti nationals in private-sector careers.

Risks

Businesses seeking to develop secondary oil and energy industries may find it challenging to operate in Kuwait if they require educated labourers but cannot hire foreign workers. Presently, Kuwaiti nationals may not seek out training in various fields that are unrelated to public-sector work due to the preferential attitudes toward state careers.

Mitigation Strategies

Potential business interests must prepare for the challenges of a limited workforce. Foreign developers that want to engage the secondary industries related to oil/energy development will need to find capable employees to manage operations. Investing in professional training directed at Kuwaiti nationals can generate an oil/energy talent pool from which businesses can draw. The introduction of more Kuwaiti citizens to the private oil/energy sector addresses the government’s concerns about low employment rates among nationals.

A partnership between private secondary oil/energy industries – such as consulting firms – and the government of Kuwait allows for the design of a career transition framework. Skills gained in the public sector could be adapted to fit private-sector oil/energy positions in marketing, engineering, human resources, and training. Hiring Kuwaiti citizens with upgraded skills and training mitigates the challenge of the government’s anticipated restrictions on the admission of educated expatriates.